Courtyard Urbanism--an Introduction

Why and how I became a courtyard urbanism advocate.

Around 2022–2023, I became increasingly aware of the real estate pressures that were driving families out of the city and into the suburbs, and of the urban planning and architecture norms that exacerbated these real estate pressures.

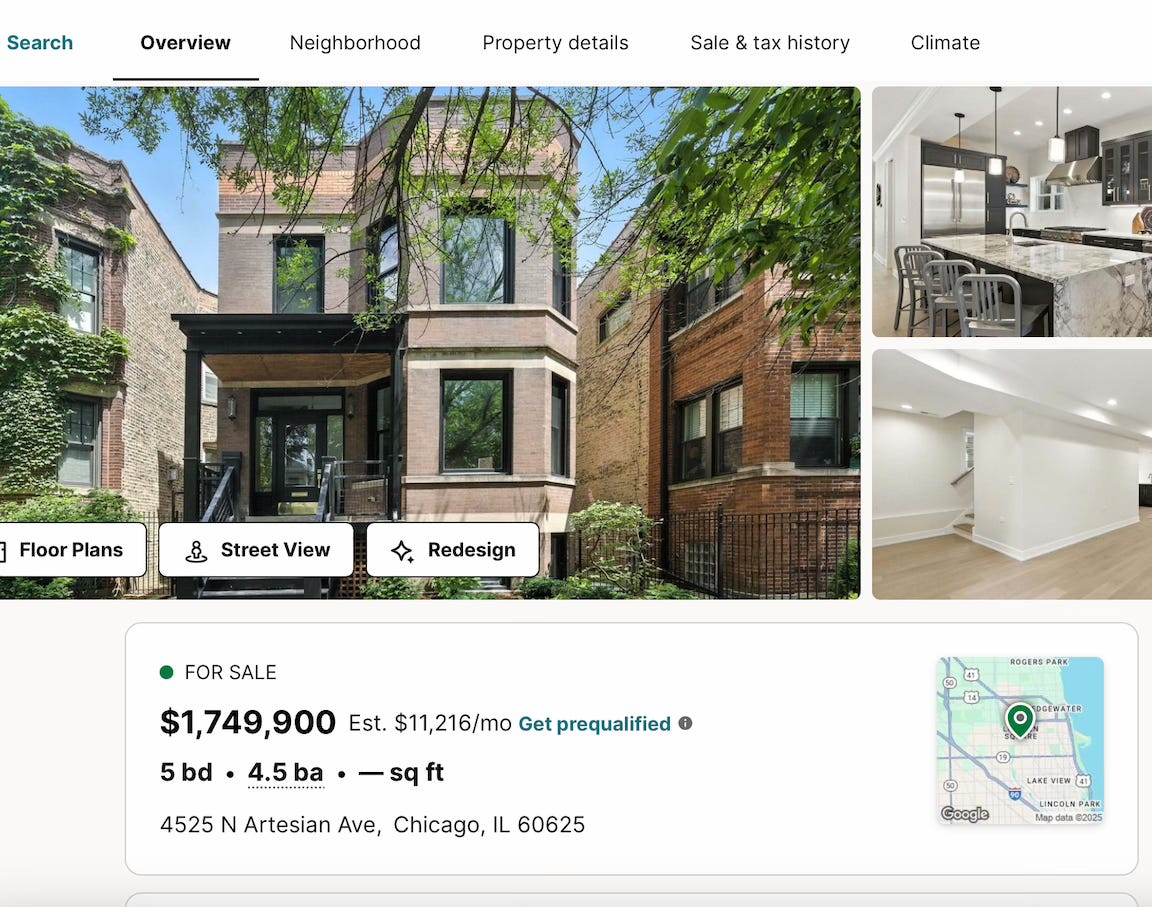

At that time, I was a stay-at-home mom raising three young children and a dog in Chicago’s Lincoln Square neighborhood, where my husband Pete and I had bought a home in 2017. As our kids reached elementary school age, I watched many families move to the suburbs because they could not afford to stay in our neighborhood, where housing stock is limited to small, yardless apartments and unattainably expensive single-family homes. At neighborhood playgrounds, chatting with parents as our kids played, I heard countless iterations of the same story: a family loves the neighborhood, wants to stay in the city, but they have outgrown their 2BD condo and are moving the suburbs because they cannot afford a downpayment on a $1M+ single-family home. The families who stay in the city tend to be very small or very fortunate.

The urban family exodus bothered me because I had observed, while living and traveling in Europe in my 20s, that many European families raise children in spacious apartments with shared courtyards in the city centers. These urban family homes were made possible by the perimeter block (aka courtyard block)—a building form common in European cities but rare in the United States. Each block is enclosed by 10 to 20 apartment buildings, typically 4 to 6 stories tall, built wall to wall to form a continuous perimeter around a central courtyard. Because the buildings are wide yet shallow, each unit usually has a front façade facing the public street and a rear façade opening onto the private courtyard. In this way, European courtyard blocks offer the functional equivalent of a “big house with a yard” while preserving the density and mixed-use character essential for walkable, affordable urban neighborhoods. Comparing this model with the “freestanding” structure of American city blocks, I came to believe that American urban design—shaped by zoning laws, building codes, and architectural conventions—effectively prevents the kind of family-friendly density that supports successful cities.

Realizing that no one else was writing about this topic, I began publishing opinion pieces in 2024 for the Chicago Tribune and other outlets, while also posting regularly on X.com.1 I initially focused on local concerns, making the case that Euro-style courtyard blocks offer a compelling solution to Chicago’s family flight problem. As my social media presence grew—reaching 10,000 followers in just 14 months—the scope of my work expanded. I now argue more broadly that building courtyard block housing can help America’s depopulated cities attract suburban families, with far-reaching benefits for urban life, family wellbeing, and the cultural and civic fabric of the country.

While writing about courtyard urbanism on X has been extremely entertaining, I’ve learned even more by engaging directly with my city and neighborhood. Through local urbanist groups, serving on the board of my neighborhood organization, and collaborating with elected officials and developers, I’ve worked to advocate for family-friendly courtyard apartment buildings in my own community. This on-the-ground experience has deepened my understanding of urban development and helped me build the political and professional relationships that, I hope, will eventually lead to the construction of a courtyard block building in my neighborhood in the not-too-distant future.

Why does it matter if U.S. cities are family-friendly? Cities need families, and families need cities. When families concentrate in suburban counties, cities lose the population base needed to sustain public safety, support essential services, and maintain infrastructure. The suburbanization wave of the 1960s hollowed out urban economies, weakened school systems, and depressed property values. Fewer families in cities means fewer eyes on the street, fewer students in local schools, fewer customers for neighborhood businesses, fewer homebuyers and workers, and fewer parents who are deeply invested in keeping public spaces safe and well-maintained. But if cities can create housing and neighborhoods that draw families back, they stand a far better chance of reversing the decline in school enrollment, shoring up public budgets, and generally revitalizing urban life.

Families need cities, too. While the baby boomer generation may not have fully valued walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods, millennials and younger generations increasingly do. Many of us grew up in car-dependent suburbs that lacked distinctive architectural identity, public gathering places, social diversity, and access to arts and culture. Our lives were shaped by drive-to schools, big-box retail, chain restaurants, megachurches, and sports complexes. Today, the North Side of Chicago is teeming with millennial parents who originally came to the city for college or work, fell in love with its energy and character, and now pay a premium to raise their children here. Our city kids enjoy the early independence and agency made possible by proximity to schools, parks, friends, transit, places of worship, and neighborhood hangouts. They also grow up with the social richness that comes from encountering people of all backgrounds, ages, and stages.

In future Substack posts, I’ll delve deeper into how courtyard block design can benefit cities and families, as well as the environmental and economic advantages of mid-rise perimeter blocks. I’ll share a detailed breakdown of the essential criteria for a successful courtyard block and expand on several ideas I’ve discussed on social media—such as my belief that American cities lacked strong urbanism even before the rise of cars and modernism, and the potential for stone construction to support a revival of multifamily living in the U.S. I also plan to write more about my personal experience moving from suburban Michigan to the historic center of Florence at age 23, where I worked as an au pair for a Florentine family living in a 16th-century palazzo built in a courtyard block.

To close this introduction, I want to emphasize that I’m an amateur in the field of urbanism. I’ve had no formal training in architecture or urban planning. My academic background is in literature: I hold a PhD in English from Northwestern University, with a specialization in Renaissance English and Italian texts. My dissertation focused on pastoral literature in early modern England and Italy, and one day I may write a post exploring the connections between those scholarly interests and my current focus on urbanism. Much of my research centered on urban writers (such as Machiavelli and Shakespeare) who used the pastoral genre to examine aspects of city life and the urban–rural divide.2 I completed my dissertation shortly after having my third child in four years, and chose to pause my academic career to focus on raising my children. My courtyard urbanism advocacy picks up interest threads that I’ve held all my life, but it is a new and unexpected text in my life, and I’m eager to see where the plot will lead.

Alicia Pederson, “Chicago’s Affordable Housing Plan Demands a Courtyard Block Blueprint,” Chicago Tribune, 19 May 2025, https://www.chicagotribune.com/2025/05/19/opinion-chicago-housing-crisis-courtyard/, accessed 18 July 2025.

—“The Courtyard Block Solution to Chicago’s Family Flight Problem,” Chicago Tribune, 13 Aug. 2024, https://www.chicagotribune.com/2024/08/13/opinion-chicago-family-flight-suburbs/, accessed 18 July 2025.

— “Get Family‑Friendly Density via Incremental Development: Op‑Ed,” Crain’s Chicago Business, 7 Apr. 2025, https://www.chicagobusiness.com/opinion/get-family-friendly-density-incremental-development-op-ed, accessed 18 July 2025.

It is not widely known that Machiavelli wrote a pastoral poem in the panegyric style, praising a prince, probably Lorenzo de’ Medici.

My one experience staying in a courtyard apartment with a child was great.

It was my luck that I was just speaking with local city leadership about potential redevelopments in our downtown, where I advocated for hugging the edge of the street and creating inner courtyards, to look you up to reference and find out you had launched a Substack. Though our plans involve retail, so not quite the residential courtyard blocks you write about. Excited for your future works and advancing family-friendly density in our cities!